Issue #75: I was ashamed of how I gave birth.

With Rachel Somerstein, journalist and author of "Invisible Labor: The Untold Story of the Cesarean Section"

Written by

. Edited by .Heads up: This issue talks about pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum. If it’s not the right time for you to read this, we completely understand.

It’s the height of summer — eight weeks until I’m due to give birth — and I’m sitting on the couch across from my doula, hands resting on my stomach. Sam and I have a long list of questions for her: “How will I know that I’m in labor?” “What’s your approach to pain management?” “What do you think of the hospital where I’m going to be delivering?” “What was your own birth experience like?”

On this last question, she pauses. She tells me that her daughter had been breech (when a baby is lying bottom or feet first versus head) — and when they were unable to turn her baby, she was forced to have a C-section. “It happens,” she says, “but I recently helped my sister deliver her last baby naturally. She’s a badass.”

I picture myself like her sister — the final push that lands a screaming newborn on my chest. Swiping away beads of sweat mixed with joyful tears. I tell myself I’ll only get the epidural if I need it. I picture myself like the mothers in the movies: Those women always give birth with their feet up, panting and screaming with exertion. They're never lying back, completely still, on an operating table.

Three months later, I’m in a hospital bed, fully dilated. “Are you ready to start pushing?” the nurse asks me. I’m ready; this is my moment.

Beep… beep… beep… beepbeepbeepbeepbeepbeepbeepbeepbeepbeep!

With each push, the beeping from the monitor accelerates. The nurse and my doula work together to help me shift into a new position. Each time I push, the baby’s heart rate spikes. The beeping speeds up again.

“Is that normal?” I ask. No one says, “No, this isn’t normal” — which I’m grateful for. We take a break, then try to push again, but the baby’s heart rate quickly spikes, an indication of distress. It becomes clear that a vaginal birth is no longer an option.

As the operating team rattles off a series of disclosures and preps me for what is about to happen, our doula pulls my husband aside. “They’re probably going to ask you if you want to cut the cord,” she tells him gently. “When you walk around the operating table, look straight so you don’t see Aliza’s body.” (Sam remains extremely grateful for this advice.)

The implications of how Jude was delivered didn’t hit me immediately — I was riding a powerful cocktail of drugs and adrenaline. It was only weeks later that I began processing it.

When I share my birth story with friends, I talk about how I felt in the moment. Yes, labor was difficult. I went through several barf bags. But we got through it. Sam was incredible: squeezing my hand with each contraction, helping me breathe as the epidural went in, and keeping me calm on the operating table. I tell them I’m grateful that the medical team remained steady, never making me feel like my life, or my son’s life, was truly in danger — even if they were. And I tell them about stroking Jude’s cheek when Sam brought him to me at the head of the operating table after delivery. Watching as Sam fed him his first bottle.

I don’t talk about the complex emotions that arose afterwards. They’re difficult for me to reconcile with. I’m disappointed, sad, and jealous of other moms who gave birth vaginally. Am I still a badass? Each time my hand glides over my scar, I wonder. Intellectually, I know I am. Emotionally, I’m not sure.

“I can’t believe you had a C-section,” friends tell me, unaware of how these words might sting. I still can’t really believe it either.

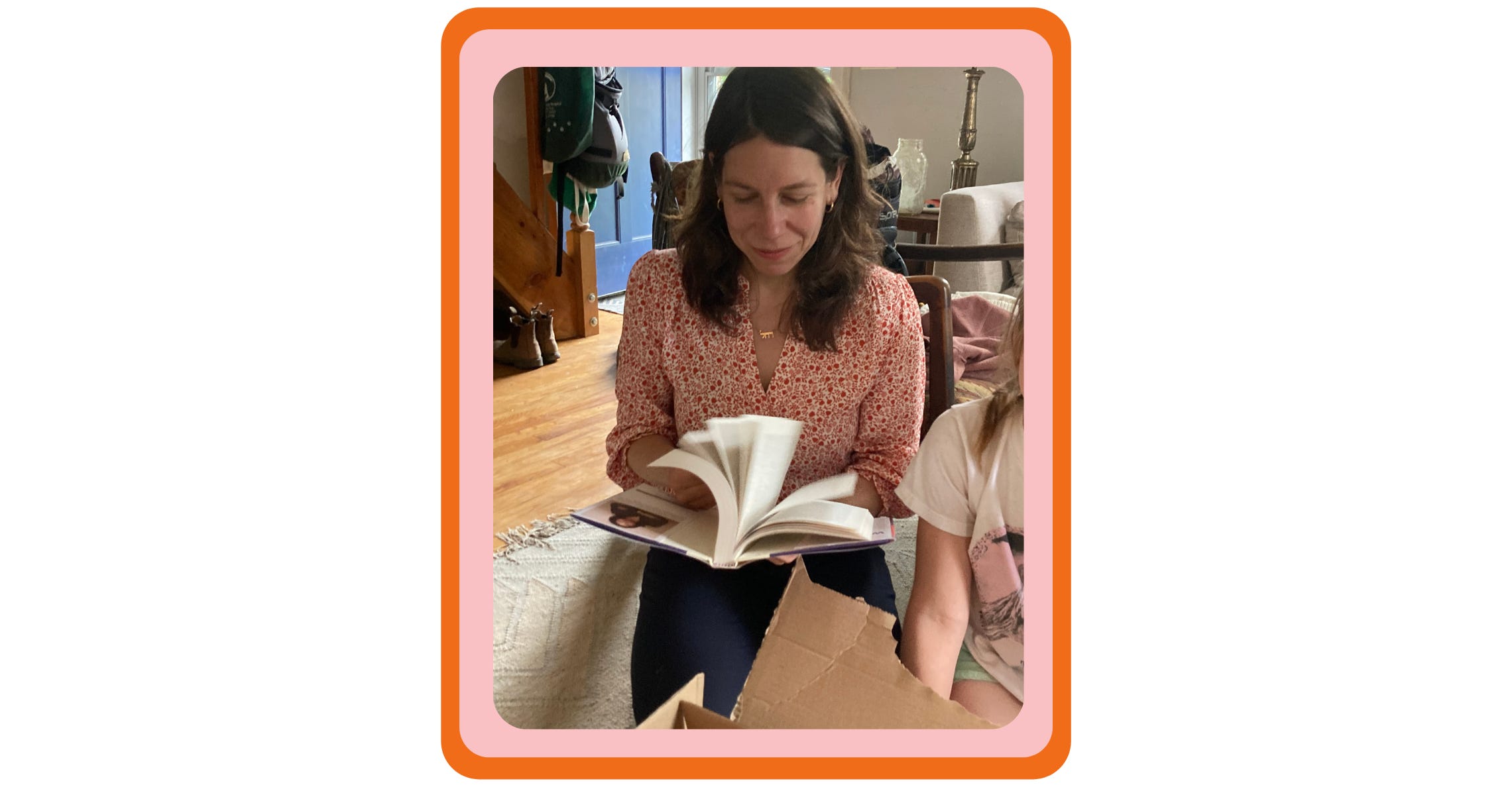

, PhD, didn’t know any of this about me when she reached out to talk about her new book, Invisible Labor: The Untold Story of the Cesarean Section. Invisible Labor is a breakthrough investigation into the history of reproductive care in the United States stemming from her traumatic labor and delivery of her first child via C-section.Today, Rachel is a writer and associate professor of journalism at the State University of New York - New Paltz, as well as a mom of two. We sat down to talk about societal misrepresentation and misperception of C-sections, what it was like to talk to other mothers for this book, why she wasn’t always sure she wanted to be a mother — and how parenthood has since shaped her career…

On why our conception of C-sections needs to change:

One in three births in the United States is via C-section. C-sections are the most common operation in the entire world. And yet they largely don’t figure in with our representation of birth — at least not in the United States.

If you have an unmedicated vaginal birth, it’s like you won gold at the Olympics. If you have a C-section, it’s like you failed to medal. And that’s insane, right? You were pregnant. You gave birth to a baby. You kept the baby alive. You kept yourself alive. Your body did an incredible amount of work and recovered from a serious operation.

We have to respect C-sections: their impact on birthing people, the fact that they’re an invasive surgery, they shape your reproductive life, and they’re not the “easy way out.”

On why she never expected to write this book:

I went into pregnancy and the delivery room completely expecting to have a vaginal birth. (I would have called it, at the time, a “natural” birth. That’s a terrible word to use. It is a vaginal birth.) I was so prepared for a vaginal birth that I’d dowsed pads in witch hazel and set them aside in my freezer for when I got home. [Witch hazel can help with pain and discomfort after a vaginal birth.]

When that didn’t happen — when I had an extremely traumatic C-section — I had a really hard time wrapping my mind around both what it meant for my body and what it said about my body that I did not have the experience I’d expected or my healthcare providers had prepared me for.

I knew that it said nothing about my character, how much I’d wanted to have a vaginal birth, or how “fit” or “good” I was. But it took me a long time to unpack all of that. The stereotypes and stigmas I held onto were part of why I felt so badly about having a C-section.

On the initial shock of a pregnancy test:

For a long time, I was not interested in becoming a parent. I thought that parenting and motherhood and babies were boring and that I could either be an intellectual and have big ideas… or I could be a mom.

When my husband and I did decide we wanted kids and then got pregnant very quickly, it wasn’t like, ‘Yay! I’m pregnant!’ I wasn’t ready. I’d just started my job as a professor, I was 33 years old, and I felt like I was still getting my feet underneath me. I worried it would completely detonate my career.

Becoming a parent, though, has opened things up to me [personally and professionally] that I never would have imagined. Yeah, there are times it’s super boring to hang out with your kids. But there are so many other times I’ll think, ‘Whoa, you’ve lifted a veil on another dimension that’s been around me the whole time.’

On bringing personal experience into her research:

I came up in [a journalistic] culture that said not to talk about any personal connection that you might have to a topic. As a journalist, you were told to be objective.

After I had my son, I was working on another academic book. I was struggling to stay motivated. And I had this moment of, ‘Why am I doing this? I’m denying that the C-section is the most important thing that ever happened to me, and that I’m a different person now.’ That helped me realize that I needed to put my academic book in a drawer. [leading to] Invisible Labor. I think it’s absurd that we wouldn’t bring our lived experience into reporting on stories — without it, so many important stories would otherwise be overlooked.

On the importance of talking to other moms:

As soon as I started talking with other moms — and these weren’t necessarily formal interviews, just hanging out at a birthday party or the park — I learned that what I’d felt after my C-section was not unique. The feelings that I’d had [after the C-section] were really, really common: of feeling unprepared, or like I’d messed up, or my body had failed me.

There were a lot of tears from the women I spoke to. It wasn’t like, ‘Oh, this is too painful to continue.’ It was more like, ‘These feelings are still really present.’ That was even for women whose C-sections were in the rear view, who’d moved on and gone through other stages of life and parenting.

On the dangers of labeling something “natural” — or not:

[The conversations around childbirth] felt very similar to ones around nursing. A lot of women I talked to were like, ‘You fed your kid formula and you had a C-section? Oh, you’re one of those moms.’ In other words, ‘You’re artificial,’ or ‘You’re uncaring.’ I don’t believe those things — but I did feel an enormous pressure to breastfeed, especially after I’d had a C-section. This whole natural thing can be really damaging. Like breastfeeding, if you want to do it, and you can do it and it works for you, that’s great. But formula — when you have access to clean water — is also great. I wish there’d been more images of women giving their babies a bottle when I was immediately postpartum. I think that would’ve really helped me.

We ended up doing some combination feeding, but I should’ve been giving my daughter formula way earlier. I really needed to sleep, and I was not sleeping at all because I was trying to nurse all the time. And in fact, when we started combo feeding, it helped me breastfeed for longer because I slept — I was able to physically recover — and I realized I didn’t have to completely stop.

On the physical — as opposed to emotional — impact of C-sections:

When I was pregnant, I was [primarily] worried about losing the weight afterwards. And in retrospect, I had no idea the ways that my body would be permanently changed, or the ways that I’d genuinely think, ‘I appreciate my body — my body made me a mother.’ A lot of women I’ve spoken to felt unprepared for how their bodies changed after the C-section.

In my book, I also go into the many downstream effects of surgery. It can make it harder to get pregnant again. It can cause issues with subsequent pregnancies. Some people have chronic pain. And so many of the moms that I talked to were dealing with all of this on their own or trying to piece together where they’d even go for this type of problem because postpartum care is such a mess.

This misperception that C-sections are the easy way out sets up a ridiculous competition, and we don’t need that. After a C-section, you can’t unload the dishwasher. You can’t pick up a toy. And you know, birth is just going to hurt, period. It just is. However you have a baby, it’s tough, and it should be respected.

I wanted my conversation with Rachel to keep going. I’m still grappling with my own experience giving birth. The lingering confusion, guilt, and disappointment of having a C-section… those emotions are still there. But talking to Rachel has made me feel seen and validated, a gift I want to pass on to other moms — both present and future.

We asked Rachel to share the works that have inspired her lately, plus the best gift she thinks you can give a friend…

An article or work that inspired her:

Linda Villarosa recently wrote an excellent New York Times Magazine piece [gift link] about the connection between chemical hair straighteners and reproductive cancers. She profiles the researchers — primarily Black women — who came to the topic from their own lived experience. It was such a great example of why we need diversity in all fields and how personal experience can inspire work even in “objective” professions like science (or journalism!) Plus, it’s an excellent piece of reporting.

I’m also inspired by the photography of Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin. As a duo (they’re no longer together), they played at the edge of nonfiction/fiction, using “real” archival images to interrogate the past and the present. Their work inspired me to think about how nonfiction, and history in particular, could be inventive, creative, provocative — everything but dry.

What she’s currently reading:

I just started Colm Toibin’s The Master, which is about Henry James. (I came to it after having just finished Toibin’s excellent new book Long Island.) And I’m looking forward to reading Jill Ciment’s memoir Consent.

What she’s listening to:

My kids (“Mom. Mom. Mom. Are you looking? Mom. Mom.”)1 Otherwise, Belle & Sebastian, especially the song “Your Cover's Blown,” which I could listen to on repeat forever.

The best gift she ever received from a friend:

Hands down, the meal trains that friends set up for me after the birth of each of my children.

To learn more about Invisible Labor: The Untold Story of the Cesarean Section and Rachel’s incredible advocacy efforts, check out this exhaustive interview with

as well as Rachel’s audio interview with Tonya Mosley on NPR. (In case it wasn’t clear already, she’s a badass.)If you enjoyed Rachel’s interview, you might also like:

Aja and I publish twice a week. There are a few ways to let us know that you’re enjoying Platonic Love: “like” this post, leave a comment, share Platonic Love, and/or upgrade to a paid subscription. Thank you for reading, and we’ll see you on Monday!

Rachel shared these answers with us at “the time of year when there is no more camp and not yet school.”

Thank you so much for this post. About a year ago I had a c-section that was planned and started (for 36 hours) as a home birth. The birth wasn’t traumatic in any way and yet I still felt (and feel) like I’ve failed. Once I got home, barely able to move (thank god for parental leave for both parents), breastfeeding also started to go downhill for a month or two. Failing at two natural things at once - that’s what it felt like. Conversations like yours I think are so important to validate experiences like mine.

I just wrote a post about my positive c-section experience and a separate post about my problems with breastfeeding. I hope you continue to feel more peace about your choices and that all of us who have c-sections can continue to ignore the misplaced judgment of others who know nothing of our business in our own bodies. Congrats to you and your happy face scar 🫶🏻🩵